Educators hold the responsibility for starting the conversation about employing effective and used Maker Spaces in schools. They are required to advocate the benefits of inclusion as well as set up growth, process-valued, flexible mindsets in their children so that they are ready to tackle the learning challenges and freedom that they may encounter in a Maker Space.

Classrooms should embrace the Maker Movement and constructionist learning opportunities by creating an open space where students can attend to varied, complex and authentic problems and projects. Every room can be a maker space where there are appropriate materials , time, flexibility, and a value for hands on learning / learning through doing. These elements are part of constructivist and constructionist pedagogical approaches (Bower, Stevenson, Forbes, Falloon, & Hatzigianni, 2020. Both pedagogical approaches place students at the centre of learning, and value the process of learning and the development of a meaningful product.

In a Maker Space, students are empowered to create through and explore STEAM learning areas, interweaving physical and digital technologies to develop skills, map concepts and design artifacts (Bower, Stevenson, Forbes, Falloon, & Hatzigianni, 2020). There is a large emphasis on collaboration and communication, whether that be brainstorming between peers, group work, peer reviews or presentation to the wider community (Bower, Stevenson, Forbes, Falloon, & Hatzigianni, 2020).

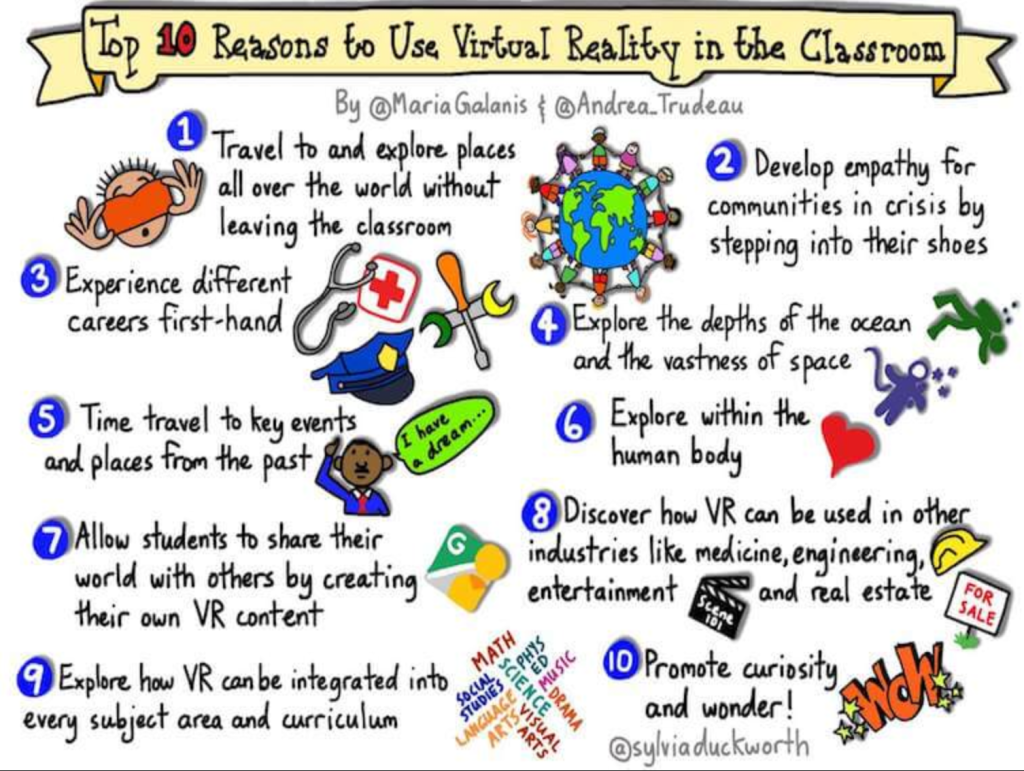

Apps and considerations that should be on teachers’ radars:

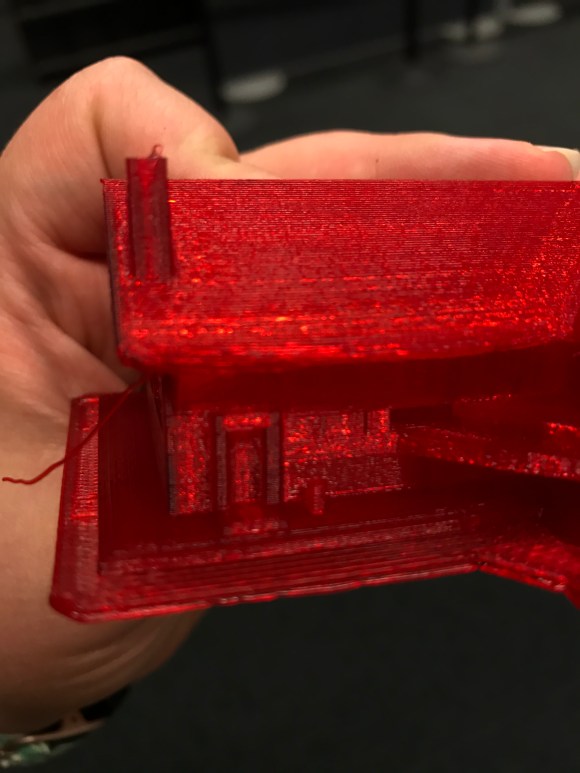

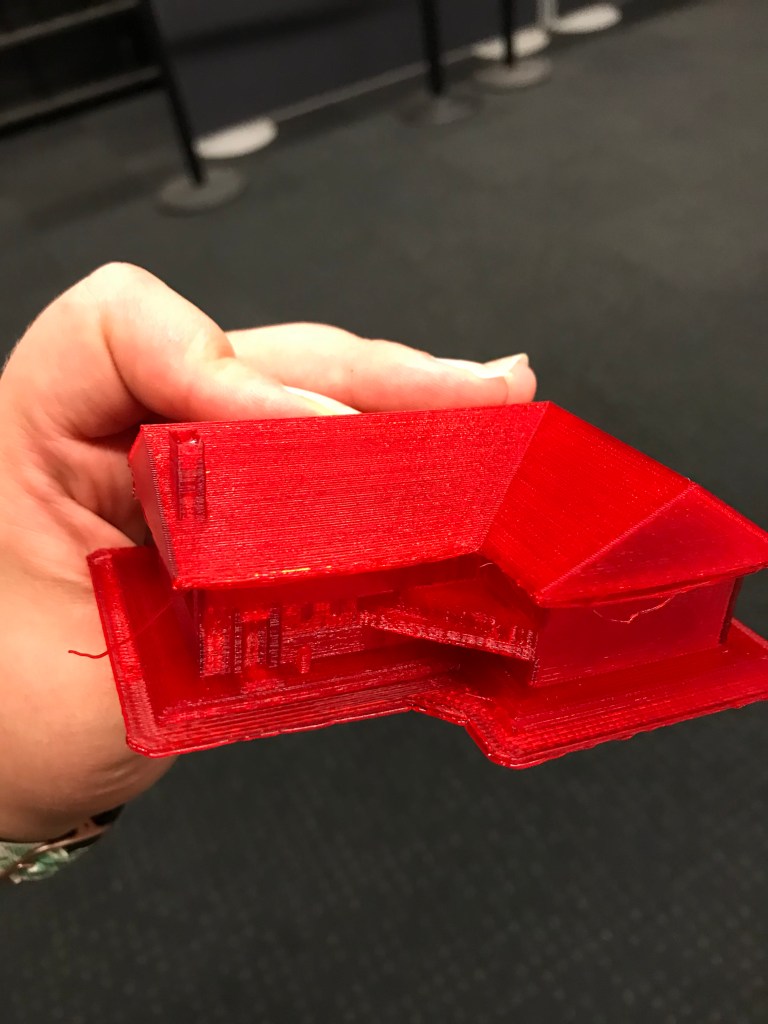

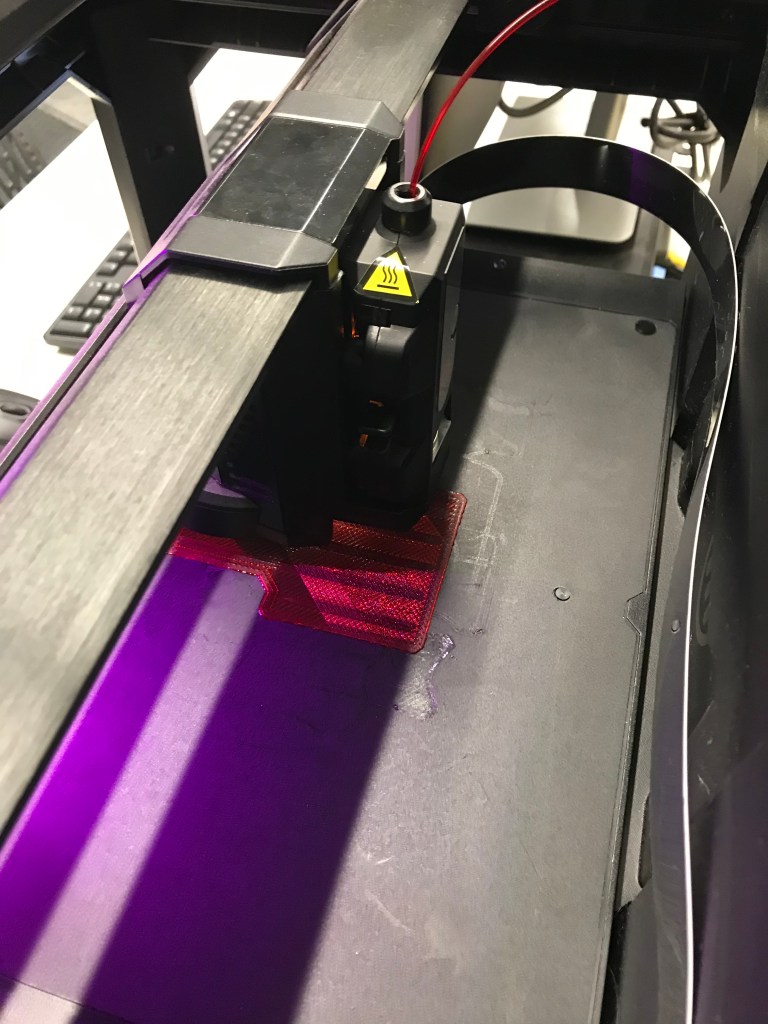

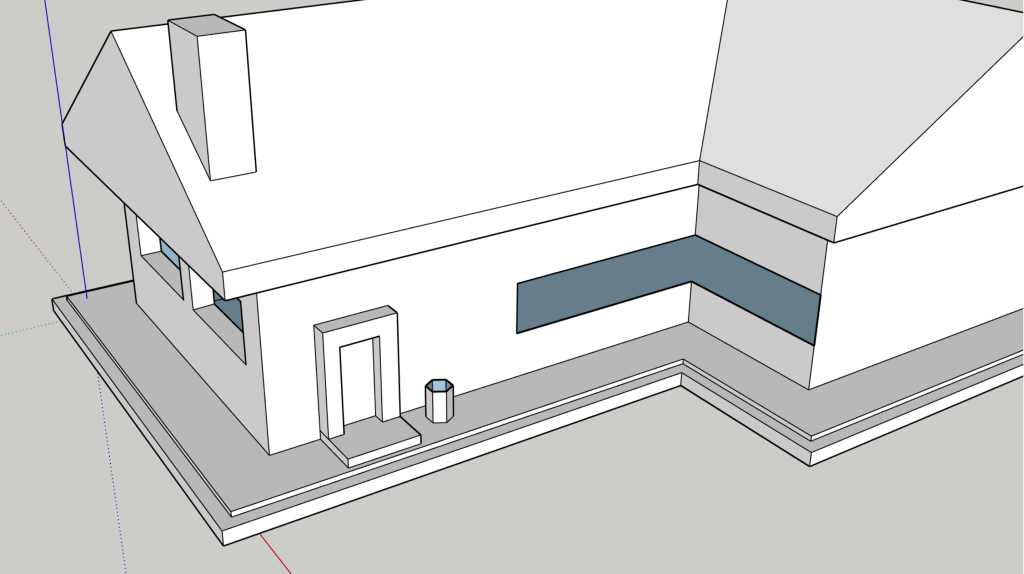

| Additive and Subtractive Technologies 3D printers, laser cutters, computer-contolled lathes etc. | Thingiverse.com – provides an abundance of files (of 3D objects) which can be adapted and remixed. Sketch Up – allows users to form 3D designs that can then be printed out AR & VR apps – these can be used to construct 3D prototypes to scale, and then the files be transformed into printable format (cospace etc) |

An authentic, project provoking inclusion to a maker space could be a ‘ Lost and Found and Broken and Fixed’ box. Students from across the year groups could bring in their broken toys, machines, small furniture etc, and a station in the maker space could be creating replacement parts and tools with the 3D design and printing technologies to fix or improve the damaged items. The social context adds some extra authenticity to the mini-projects.

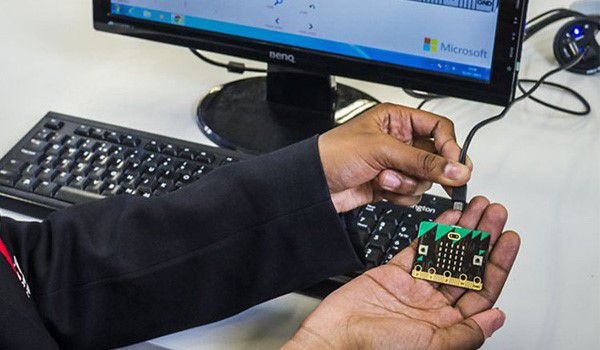

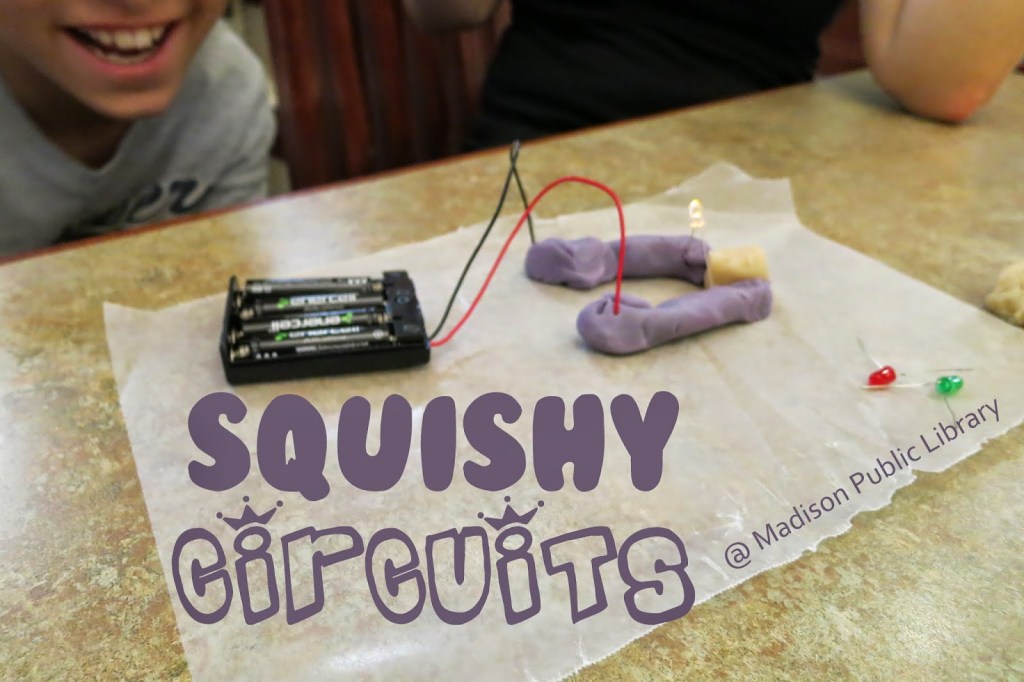

| Robotics Kits | – building interactivity and function into everyday objects – Lego WeDo and Mindstorms, Neuron are limited in their creativity potential due to the way the blocks function – micro controllers such as Microbit and Arduino allow for a deeper observation of the electronic elements, and their programmable nature open up creative possibilities (Arduino Projects for Kids) – opportunity to develop robots / machines to interact with surroundings from existing repurposed and reused materials – circuits coming alive through Squishy Circuits and Makey Makey |

Lego Mindstorms

Make Blocks

Makey Makey

Microbit

Arduino Microcontroller

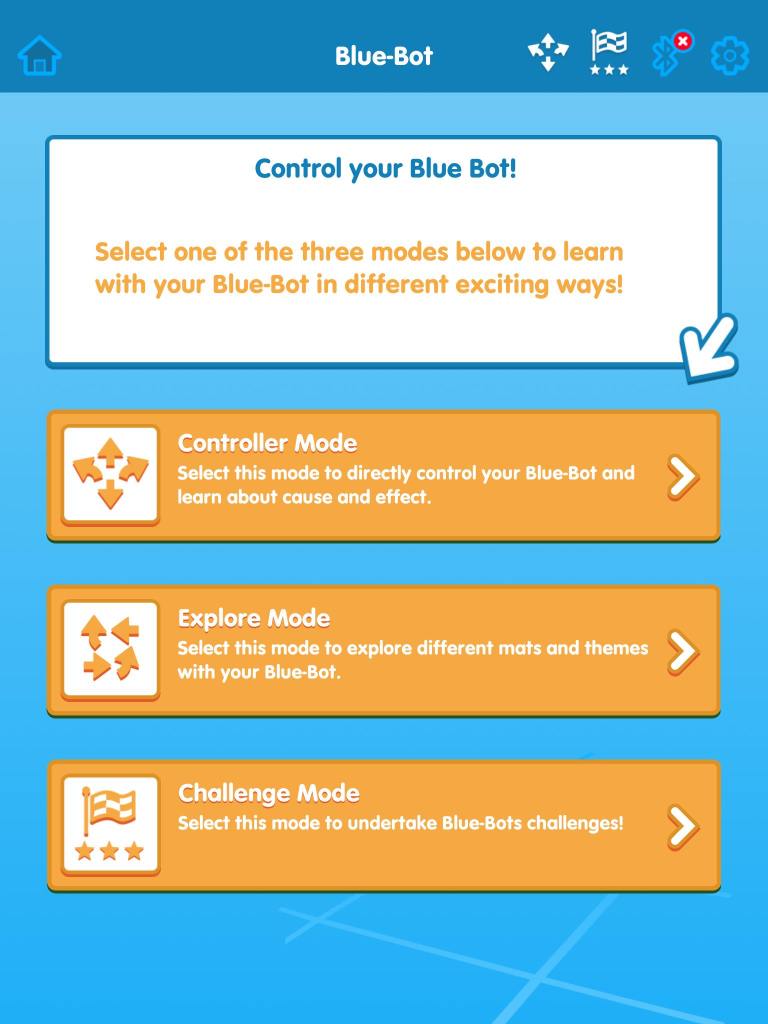

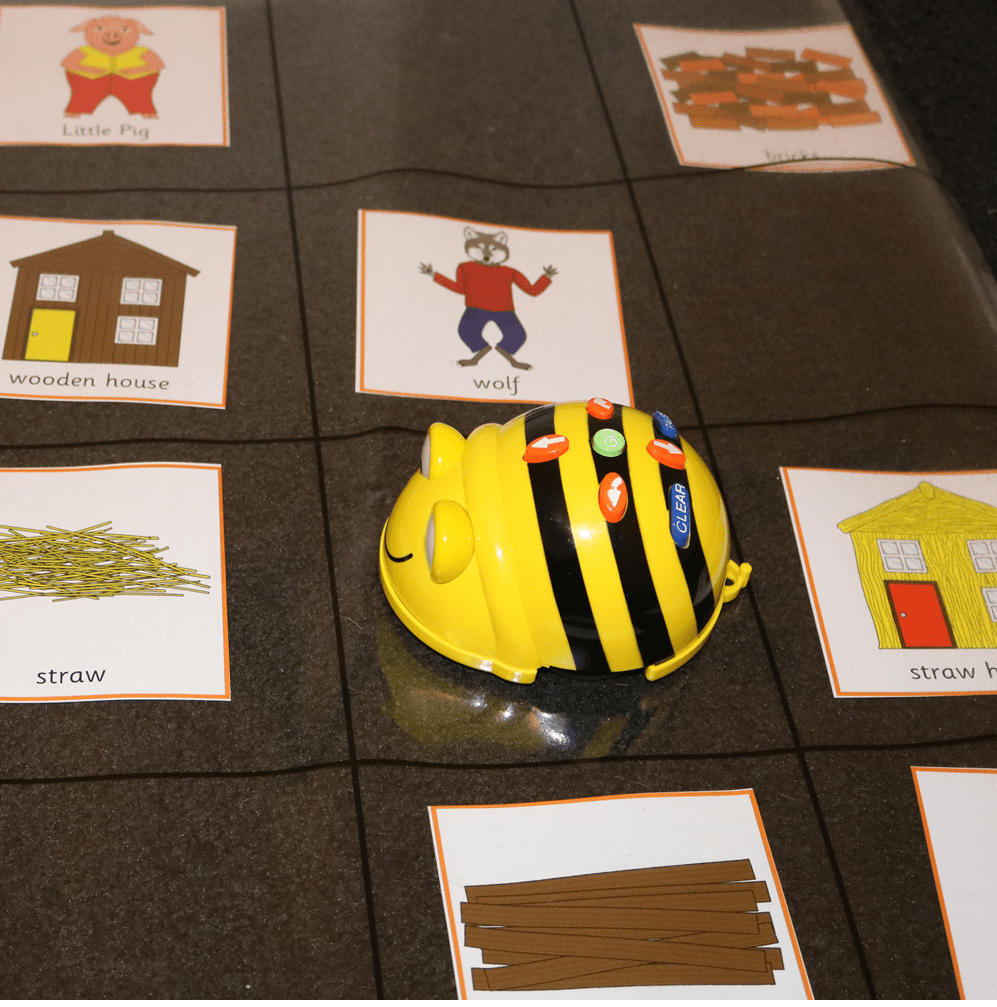

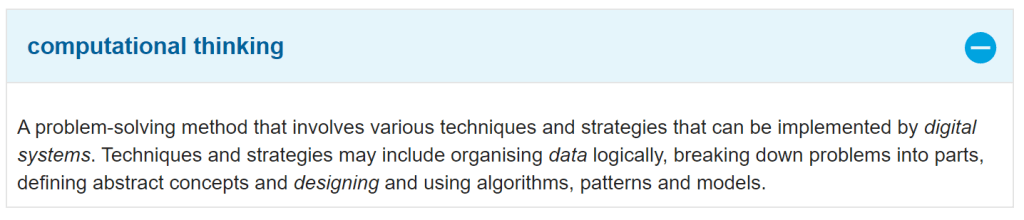

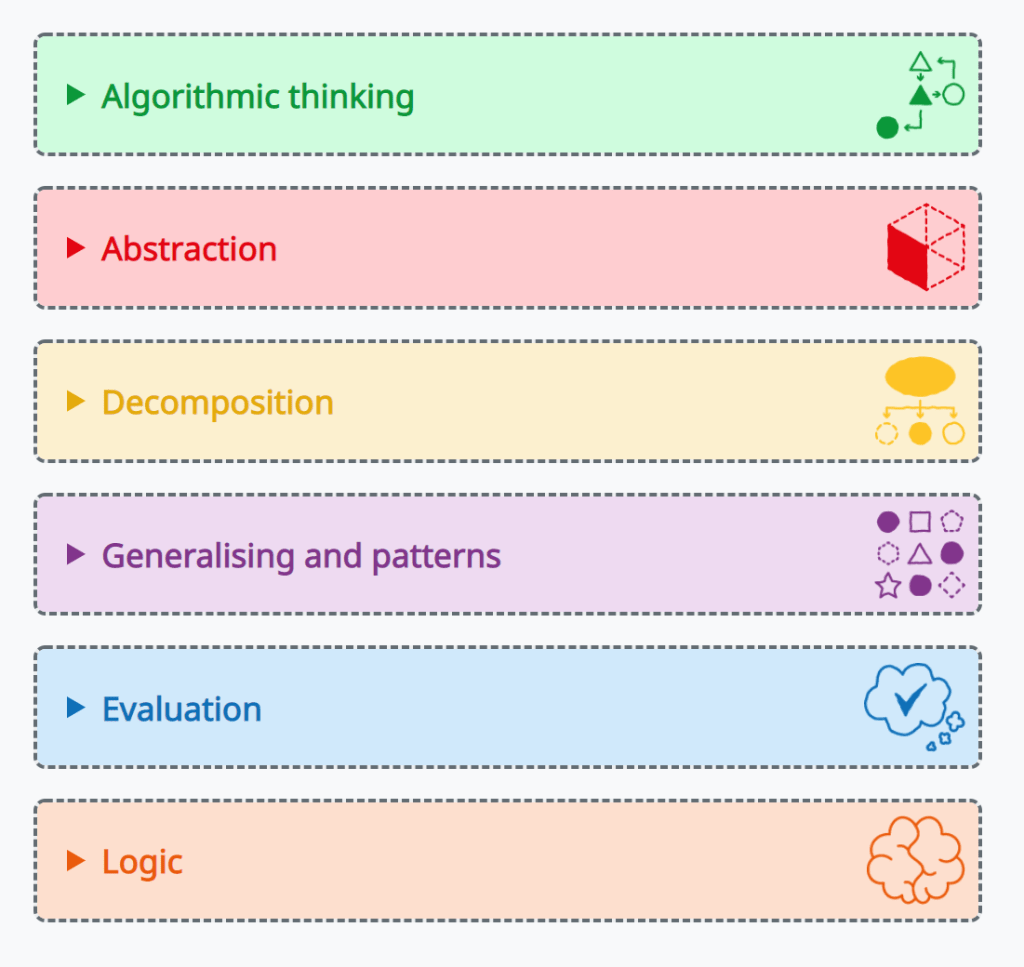

| Programming | Programming is a skill that is developed over a long period of time. The more exposure students get to a variety of programming platforms and challenges, the better versed they will be, making them more equipped for the modern digital age. Computational thinking skills can be built through these experiences and are a valuable toolkit to continually develop as they can be applied to problem solving challenges in an abundance of areas of life. – hour of code – code.academy – CS Unplugged – Scratch |

Classroom Implications

Teachers should be active developers and facilitators of creative thinking in Maker Spaces. Quite often, explicit instruction of digital and physical technologies as well as teacher models of thinking and designing are needed so that students can access the learning by doing (Bower, Stevenson, Forbes, Falloon, & Hatzigianni, 2020). Whilst some tasks presented by the teacher or approached organically need to be at the frustrational level so that students have the opportunity to work through that, they should also begin to form a toolbox of capabilities in various areas of digital design and production so that they can attend a variety of tasks in a Maker Space (and not be demotivated by the perceived difficulty of a task) (Bower, Stevenson, Forbes, Falloon, & Hatzigianni, 2020).

An emphasis should be placed on student-centered, inquiry based learning, where play and experimentation is valued (Bower, Stevenson, Forbes, Falloon, & Hatzigianni, 2020). A plethora of offline and online opportunities and systems should be provided; (younger – in particular) students require physical manipulation of objects before abstracting ideas and moving to digital platforms (Bower, Stevenson, Forbes, Falloon, & Hatzigianni, 2020).

References

https://www.iste.org/explore/In-the-classroom/The-maker-movement%3A-A-learning-revolution

Bower, M., Stevenson, M., Forbes, A., Falloon, G. & Hatzigianni. M. (2020). Makerspaces pedagogy – supports and constraints during 3D design and 3D printing activities in primary schools. Educational Media International, 57(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2020.1744845